“I am convinced that in the somber decades to come, the end of the world ‘as we know it’ is a distinct possibility…when this time comes (it has already come in my opinion) we will have a lot to learn from people whose world has already ended a long time ago – think of the Amerindians whose world ended five centuries ago, their population having dropped to something like 5% of the pre-Columbian one in 150 years, the Amerindians who nonetheless, have managed to abide, and learned to live in a world which is no longer their world ‘as they knew it.’ We soon will all be Amerindians. Let’s see what they can teach us about matters apocalyptic.” (Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, 2014).

If we are to take heed of Eduardo Viveiros de Castro’s suggestion that we might be able to learn something about ecological sustainability from the life-ways of our ancestors, as well as from the cultures of indigenous peoples around the world, we are inevitably going to bump up against animist worldviews. The term animism derives from the Latin root word anima, meaning soul, and in its scholarly usage has referred to the belief that the world is populated by ‘spirits,’ or, to use a more recent (and somewhat more encompassing) term, ‘other-than-human persons’ (both empirical/physical and non-empirical/physical). For an animist the world is alive, so that rocks, trees, animals, plants, mountains and rivers could all posses personal attributes, desires, fears and needs, just like human persons. From an animist perspective, ecosystems can be understood as complex communities of persons in dialogue with one another, and we are participants too.

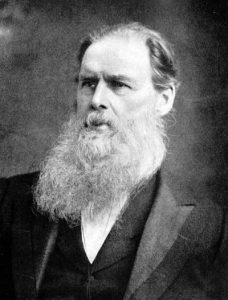

Animism was first popularised as a scholarly category by the anthropologist Edward Burnett Tylor (1832-1917), who saw the belief in spiritual beings as the very earliest expression of religious thought. Indeed, for Tylor there was little distinction between traditional indigenous religions and the major world religions – he considered that all religions, from tribal religions to Catholic Christianity, could in their essence simply be defined as the ‘belief in spiritual beings.’ Tylor’s version of anthropology, however, was closely wedded to a form of social evolutionism known as Developmentalism, that was particularly popular during the latter half of the nineteenth century (Stocking Jr, 1982, p. 97-100). According to this view, European (and especially British) culture was understood to be the pinnacle of social and cultural development, while other non-western and indigenous cultures were seen as somewhat backward, irrational and misguided, but that nevertheless had somehow survived into the modern day. Sadly, such a view ultimately distorted Tylor’s perception of the animistic worldview(s) he wrote about in his books, and it wasn’t until much later that scholars began to re-engage with animism without such a developmentalist (maybe even colonialist) attitude.

In his 1960 publication ‘Ojibwa Ontology, Behavior and World View,’ the American anthropologist Alfred Iriving Hallowell (1892-1974) described how for the Ojibwa people of central Canada the world is populated by persons ‘not all of whom are human.’ Hallowell famously gives the example of his conversation with an old Ojibwa man:

‘I once asked an old man: Are all the stones we see about us here alive? He reflected a long while and then replied, ‘No!’ But some are’ (Hallowell, 1960)

The old man’s answer to Hallowell’s question had a lasting impact on the anthropologist. The old man’s response suggests that for the Ojibwa people, stones have the capacity for life – their worldview leaves open the possibility that stones, trees, mountains and so on can be persons, and as such ought to be granted the same respect as a human person, just in case. Interactions with features of the landscape, therefore, must be understood as interactions between persons, as relationships.

More recently, scholar of religions Graham Harvey has taken up the themes of Tylor and Hallowell’s work (amongst others), with the formulation of his ‘New Animism.’ New animism differs from Tylor’s ‘old’ animism firstly through not assuming a social developmentalist perspective that sees animistic beliefs as symptoms of primitive and irrational thinking, and secondly by shifting its focus away from the somewhat problematic notion of ‘spirits,’ towards the much more encompassing idea of ‘persons,’ which may include persons who are ‘other-than-human.’ Harvey writes:

“Animists are people who recognise that the world is full of persons, only some of whom are human, and that life is always lived in relationship with others. Animism is lived out in various ways that are all about learning to act respectfully (carefully and constructively) towards and among other persons. Persons are beings, rather than objects, who are animated and social towards others (even if they are not always sociable). Animism…is more accurately understood as being concerned with learning how to be a good person in respectful relationships with other persons” (Harvey, 2005, p. xi).

The underlying relational philosophy of the new animism (which is only ‘new’ to academia), represents the antithesis of the materialistic-industrial-consumer philosophy that has dominated Euro-American attitudes to the environment for the last 200 years, and would seem to offer a route towards the kind of ‘Deep Ecology’ advocated by Arne Naess.

Many in our post-industrial society are likely to feel uncomfortable with the notion of attributing personhood to the various components of our ecosystems, but we can take a hint from the Ojibwa and treat ecology as if it possesses personhood, without necessarily believing that it does. If we were to adopt a relational attitude, and interact with rivers, streams, trees, animals, soils and so on as if they are persons, our behaviours and actions would also necessarily be altered as a consequence. We wouldn’t want to pump sewage into another person, for example, or destroy the home of person, or abuse, misuse or exploit another person. When we think in relationships, we realise that we need to develop good relationships with the other persons in our ecosystem – prosperous, mutually beneficial relationships. Much as in systems thinking, a relational worldview makes us aware of our own interconnected and interdependent relationship with the world around us. So, even if we don’t believe that the tree in our garden is a person, or the river in our village, or the sky above our heads, we can still behave as if they are – our actions can be informed by a relational ecocentric perspective, rather than a purely anthropocentric one.

Granting Personhood Status to Ecosystems

An interesting recent development is the gradual granting of personhood status to key ecosystems by some of the world’s governments. For example, the Whanganui River in New Zealand, known as Te Awa Tupa amongst the indigenous Maori people, was the first river to be granted the legal status of personhood. The Maori people, whose lives are dependent on the river system, and who have always thought of the river as an ancestor, have been fighting for the last 140 years for the river to be treated with the respect that it deserves as an ancestor and living entity, a request that was finally granted on Wednesday 15th March 2017. Gerard Albert, the lead negotiator on behalf of the Whanganui tribe explains:

“We can trace our genalogy to the origins of the universe, and therefore rather than us being masters of the natural world, we are part of it. We want to live like that as our starting point. And that is not an anti-development, or anti-economic use of the river but to begin with the view that it is a living being, and then consider its future from that central belief.”

What this means for the Whanganui River is that, as a legal person, any damage inflicted on it is equivalent to damaging a human being. What if we could do this for our own rivers, forests and mountains? What impact would it have on our relationship with our local ecosystem? Might it help us to achieve the goals laid out by the Paris Climate Agreement? Would it encourage us to behave more responsibly? To change our use of chemical fertilisers, for example, which may leach into the river from farmlands? I think it would.

Within days of the New Zealand government’s decision to grant personhood status to the Whanganui River, a court in Northern India ordered that the sacred River Ganges, and its primary tributary the Yamuna, also be granted the legal status of personhood, as well as glaciers and other ecosystems, precisely so that they can be protected and preserved for the benefit of future generations, and for our global system as whole.

Briefly turning to the theme of our local folklore, we might be surprised to find that many of our most familiar landscape features have already had their personhood recognised by our ancestors. Bala Lake, just over the Berwyn mountains, for example, is inhabited by the great monster Tegid, and the River Severn was known by the Romans as the goddess Sabrina. What about Afon Rhaeadr, Afon Tanat and Afon Cain? Are these persons too? If so, have we been treating them with the respect they deserve? Could animist principles be a catalyst for the change in thinking required by the Paris Climate Agreement? Perhaps we should consider lobbying to have our rivers recognised as persons, and our ecosystems as complex communities of these ‘other-than-human persons,’ just as the Whanganui tribe have been doing for the last 140 years.

References

Hallowell, A.I. (1960). ‘Ojibwa Ontology, Behavior and World View.’ In G. Harvey (ed) (2002) Readings in Indigenous Religions. London: Continuum. pp. 17-50.

Harvey, G. (2005). Animism: Respecting the Living World. London: Hurst & Company.

Stocking, G.W. (1982). Race, Culture, and Evolution: Essays in the History of Anthropology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Tylor, E. B. (1930). Anthropology: An Introduction to the Study of Man and

Civilization. London: C.A. Watts and Co. Ltd.

Viveiros de Castro, E. (2014). ‘Who is Afraid of the Ontological Wolf?’

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/mar/16/new-zealand-river-granted-same-legal-rights-as-human-being

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/mar/21/ganges-and-yamuna-rivers-granted-same-legal-rights-as-human-beings

Wonderful post!

[…] When we look at the world now we look at them through Aristotle’s eyes (with a tint of Descartes), in that we interpret/intellectualize our sensations of all phenomena as containing or deriving from form and matter or ‘substance’ and that this ‘substance’ is separate from us (objective/subjective). Using Dependent Origination as a method to gain a ‘truer’, more nuanced understanding of reality than this materialist view, we can in a more inclusive and useful way, organize and understand phenomena in terms of patterns, systems and ecosystems. And when we talk about these ‘systems’ or ecosystems there is no rational reason to assume that they exist in some cold, soulless automated machine-like way. To see, feel and interact with these dynamic systems, just as many indigenous peoples do and have done, peoples who do not share our static cultural baggage , we treat them as being alive. […]